|

|

Theme: “Where Reason Fails…”

Papers:

5th December (Tues)

John Owen’s Doctrine of the Trinity and its Significance Today (Bob Letham)

Thomas Cranmer and the Anglican Enigma (Gordon Murray)

The Azusa Street Phenomenon (Stanley Jebb)

6th December (Weds)

The Puritan Doctrine of Atonement (Garry Williams)

“When is a war a just war?” (Ken Brownell)

William Tyndale – The Man who gave England her Bible (Phil Arthur)

Venue:

Friends House (opposite Euston Station)

173 Euston Road

London

NW1 2BJ

Cost: £35 (per person), £20 (students); additional £5 per day for packed lunches on request

Email conference secretary John Harris for registration and order forms: jfharris@ntlworld.com

Please register by 28th November if interested.

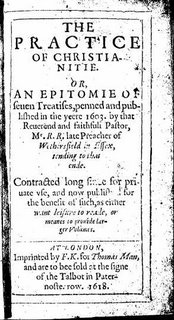

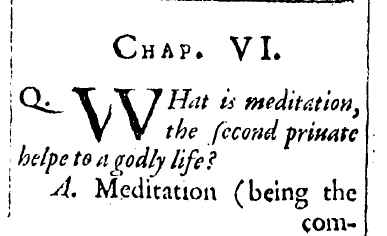

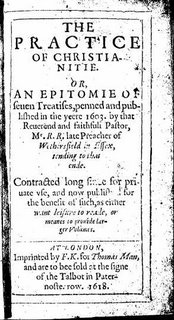

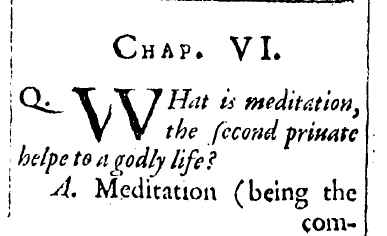

In response to John's kind suggestion, I am posting the last third of the paper I had the opportunity of presenting at the Christianity and History Forum for Scotland meeting at Rutherford House last week. It describes a method of Puritan meditation that was probably fairly well-known among the godly throughout the seventeenth century. The excerpt pretty much explains itself: I want to conclude by sharing in some detail the method of meditation that Stephen Egerton laid out in his abridgement of Richard Rogers’s Seven Treatises (called The Practice of Christianitie, 1618), which included some material from Joseph Hall’s Art of Divine Meditation (1606). Egerton’s abridgement was put in the form of a catechism, in question and answer format. The first question of Treatise 3 and Chapter 6 asks, “What is meditation, the second private help to a godly life?” (Richard Rogers had divided the means of grace into public and private categories, and meditation was considered a private duty, along with what he called watchfulness or spiritual vigilance, reading, private prayer and the like.) Egerton answers the question thus: Meditation (being the companion of watchfulness and sister of prayer), is nothing else, but a deep and earnest musing upon some point of Christian instruction, to the leading us forward towards the kingdom of heaven, and serving for our daily strengthening against the flesh, the world and the devil: or (as others define it to the same effect), meditation is a steadfast and earnest bending of the mind upon some spiritual and heavenly matter, discoursing thereof with ourselves, till we bring the same to some profitable issue, both for the settling of our judgments, and for the bettering of our hearts and lives; the very life of meditation being application, and a laying home to the conscience of the point we think upon. At the outset I’d like to point out two things that are mentioned in this summary that were very typical of almost all the teaching on meditation throughout history, especially during its development in the medieval period. First, meditation is essentially a mental exercise. Notice Egerton’s terms: ‘earnest musing’, ‘bending of the mind’, and ‘discoursed’. This is not to say there weren’t forms of meditation that involved the emptying of the mind or the transcendence of the mental faculties. So-called ‘apophatic’ and mystical approaches to meditation also have a history within the Christian church, but they were generally reserved for very mature saints and were rarely achieved or experienced. During the early modern period these alternate forms of meditation were highly suspect in the eyes of both Protestants and Catholics. The more common, pedestrian form of meditation is the one discussed here, and this required the full engagement of the intellect. Second, while meditation is carried out as a cognitive exercise, it is always supposed to lead to a change in one’s attitude or judgement, and ultimately a change in one’s behavior. Egerton calls application ‘the very life of meditation’, and says the point one thinks upon must be ‘laid home to the conscience.’ This was seen as the goal of meditation in all the literature. Writers from this period and those before wrote confidently of the power of meditation to change those who practiced it. Many religious communities within the Catholic Church were said to have been revived and reformed, primarily by a renewal of participation in this discipline. Witness, for example, the founding of the Society of Jesus and the explosion of Jesuit ministry and missionary activity in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Everyone who entered that organization underwent an intense, month-long retreat at the outset, every day of which was filled with meditation on the life and Passion of Christ, on sin, on the kingdom of God and ultimately on their place in the plan of God. This regimen was based on a work by the Jesuits’ founder, Ignatius Loyola, called the Spiritual Exercises. Several of the Catholic books that were smuggled into England were based on Loyola’s meditative techniques, including Persons’s Booke of the Christian Exercise, mentioned earlier. Egerton insisted the benefits and fruits of meditation are “manifold”,for it calls our minds out of the world to mourning, or mirth, to complaint, prayer, rejoicing and thanksgiving in the presence of God. It dries fleshly and bad humours of worldliness and earthly-mindedness. It quickens and awakens the dull and drowsy heart, that is ready to be sleeping in sin. There is no private help so available to gauge and sift, weed and purge, and as it were to hunt and ferret out of our hearts swarms of wicked and unsavoury thoughts and lusts, which otherwise will not only lodge and dwell, but also rule and reign in them; and to entertain and hold fast heavenly thoughts, which otherwise will run out of our riven heads, as liquor out of a rotten vessel.  He mentions two types of meditation, both of which he encourages all Christians to make use of. These are occasional and deliberate. Occasional meditations can occur throughout one’s day, just about anywhere. As he says, “they are occasioned by such things, as by the providence of God do offer themselves to our senses, eyes, ears, etc., as we go about the duties of our callings …” This kind of exercise entails paying attention to the things we encounter in daily life and reflecting on them for an edifying purpose. Egerton writes very little about this kind of meditation, but it did play a considerable role in the spirituality of the Puritan tradition. Thomas Manton had this to say about it: He mentions two types of meditation, both of which he encourages all Christians to make use of. These are occasional and deliberate. Occasional meditations can occur throughout one’s day, just about anywhere. As he says, “they are occasioned by such things, as by the providence of God do offer themselves to our senses, eyes, ears, etc., as we go about the duties of our callings …” This kind of exercise entails paying attention to the things we encounter in daily life and reflecting on them for an edifying purpose. Egerton writes very little about this kind of meditation, but it did play a considerable role in the spirituality of the Puritan tradition. Thomas Manton had this to say about it: God trained up the old church by types and ceremonies, that upon a common object they might ascend to spiritual thoughts; and our Lord in the New Testament taught by parables and similitudes taken from ordinary functions and offices among men, that in every trade and calling we might be employed in our worldly business with an heavenly mind, that, whether in the shop, or at the loom, or in the field, we might still think of Christ and heaven. Jonathan Edwards compiled a list of phenomena in nature that illustrated various spiritual truths, using this same kind of technique, in a work called Images or Shadows of Divine Things. For example, he noticed that lightning often strikes the tallest objects first, and felt this was similar to the way God is said to oppose the proud, and give grace to the humble. And so in this brilliant natural wonder, Edwards believed, there was a spiritual lesson to ponder and take to heart. Egerton spends most of his time describing the second type of meditation, which is called deliberate. He says it takes place “when purposely we separate ourselves from company, and go apart to perform this exercise, more thoroughly making choice of such matter, time, place, and other circumstances as are most requisite thereunto”. As the name implies, it is planned and deliberate. I’ll describe this method to you now in some detail. In answer to the question, "What ought to be the matter, or subject of our meditation?", Egerton says, not surprisingly, that Scripture should be our main source of material. Specifically, God’s nature and his works, or our own vileness and sinfulness, and "the great and sundry privileges which we enjoy daily through the inestimable kindness of God in Jesus Christ". The writings of godly men, he says, can also stimulate many holy meditations for those who read them. Now, to the method itself. The process that Egerton describes consists of two stages. The first is intended to stimulate the intellect and the second is intended to arouse the affections and the heart, that is, to cause the devotee to love what is good and to hate what is evil, according to whatever it is he or she meditates on during the first stage. And the entire exercise begins and ends with a brief prayer, thanking God beforehand for the opportunity to reflect on His truth, and asking for His assistance, which Egerton says is absolutely essential – and afterwards, thanking him for the fruits produced by the exercise, and asking him to enable one to live a life “answerable to those heavenly thoughts and desires, which one has had and expressed in the performing of this duty”. The fact that prayers are encouraged as bookends for the meditation is consistent with the Puritan conception of the means of grace that has already been mentioned [earlier in the paper], which viewed disciplines like this as necessary for spiritual growth, but as powerless by themselves without the involvement of God’s Spirit. Prayer is made, among other reasons, to acknowledge the sovereignty of God in the process of sanctification. After the opening prayer, we are to proceed to the first stage of the actual meditation, which deals primarily with the intellect. Here, the main task for us, according to the writer, is to take the subject we’ve chosen to meditate on, be it sin, or predestination, or God’s omnipotence or something else, and to think about all that Scripture has to say about that subject. We’re to let our minds range throughout the Old and New Testaments, to gather up and to reflect upon all that is said there about it. And here, Egerton suggests, it becomes useful to bring in some logic for help. He lists eight logical categories, taken from the philosophical method of a Frenchman called Peter Ramus, or Pierre de la Ramée, whose ideas were popular in the seventeenth century. Ramus’s method was seen as an alternative to traditional scholasticism, but it was actually fairly similar to Aristotelianism. Egerton’s readers are to cogitate on their subject from the standpoint of these eight logical categories. They are

- first, its definition or description;

- second, its distribution, that is, its parts or kinds;

- third, its cause or causes, especially its efficient and final causes;

- fourth, its fruits or effects;

- fifth, its class, or the subject wherein it is occupied;

- sixth, the qualities or properties adjoined to it or cleaving unto it;

- seventh, what is different from, opposite to or contrary to it; and

- eighth, what it is like.

And thus we are to muse upon our scriptural subject for some time.

Eventually we’re ready for the second stage, which involves the affections. The goal of this second and last stage, according to Egerton, is “to have a sensible taste, lively touch, and fruitful feeling of that whereof we have discoursed with ourselves, according to the former direction; that we may be affected either with godly joy, or godly sorrow, godly hope, or godly fear, etc.” He now lays out five instructions to bring about what he calls “the quickening and affecting of the heart”.

- First, we are to enter into a “lamentable and doleful complaining and bewailing of our estate, either in respect of the sin that abounds there, or the grace that is wanting”. This heightened awareness of our own wretched condition should be a natural result of the first stage of the meditation.

- Second, he says, we are to cultivate "a most passionate, vehement, earnest and hearty wishing and longing after the removal of this sin and punishment which is hated, and for the obtaining of the good things that are loved.” Now feelings of sorrow and conviction are to be trained on a specific goal, the removal of sin or the obtaining of grace and pardon.

- Third, he says, we should make "a humble and unfeigned acknowledgement and confession of our own weakness and disability, either to remove the evil, or to obtain the good proceeding from a broken, sorrowful heart”. At this point, towards the end of exercise, the meditation begins to express itself in prayer form, and now we are asked to confess our helplessness in the obtaining of what we desire – either the removal of sin or the obtaining of grace and virtue.

- Fourth, Egerton says, we should fervently petition God, "earnestly craving and begging at his hands, either the removing of the evil which our soul hates, or the obtaining of the good which it longs after”. Now the prayer takes full form.

- Fifth and finally, we are “to take cheerful confidence, raising and rousing up our souls after [all that we have experienced], such doleful complaining, hearty wishing, humble confessing, unfeigned acknowledging, and earnest craving of that we want”. Now, says Egerton, we are to look with hope and trust to the mercy of God, having faith “grounded upon the most sweet and sure promises of God, made to them that call upon him in faith, and upon the experience which the saints of God in all ages have had, of the success of their suits, who were never sent away empty, but either obtained that thing which they begged”.

So, from the intellectual analysis and reflection that a devotee has carried out during the first stage of this meditation, he or she would ideally draw out both sorrow and joy, fear and faith, during this second and final stage – and this, under gracious circumstances, would lead to a changed life. This was one form of Catholic contemplation, re-articulated through a Puritan grid.

|

|