Synopsis of The Elizabethan Puritan Movement, Parts 1-2

I’ve been meaning to post this for some time: a section-by-section synopsis of Patrick Collinson’s important, detailed history of The Elizabethan Puritan Movement. The book is divided into eight parts, each of which contains three to five chapters.

I've divided the synopsis into four bite-size installments. Of course, if you have the time, I recommend reading the entire thing.

In case you missed our 'Conventicle Q&A' with the author, check it out here.

Part One: Puritanism and the Elizabethan Church

Chapters:

- The Church of England and the English Churches

- 'But Halfly Reformed’

- The Beginnings of a Party

The common view prevailing among the English during the late sixteenth century was that the Church of England—its entire membership—were to be considered orthodox, as long as its doctrine were sound. By contrast, those who were eventually labelled puritans perceived a real difference between themselves and the nominal, lukewarm majority who claimed to be members of the church. Puritans are best distinguished from conformist Anglicans (a term that came into use in a later era), not by their theology, but by their “temperature”: they were “the hotter sort of protestants”, according to one Elizabethan pamphleteer.

The common view prevailing among the English during the late sixteenth century was that the Church of England—its entire membership—were to be considered orthodox, as long as its doctrine were sound. By contrast, those who were eventually labelled puritans perceived a real difference between themselves and the nominal, lukewarm majority who claimed to be members of the church. Puritans are best distinguished from conformist Anglicans (a term that came into use in a later era), not by their theology, but by their “temperature”: they were “the hotter sort of protestants”, according to one Elizabethan pamphleteer.There were several elements within the church that needed reforming at the beginning of the Elizabethan period. It was in financial disarray, its courts operated with a complexity that defied logic, many of its clergy were unlearned, and most importantly, there were no means in place by which to instill and enforce discipline in the leadership or the laity. In addition, semi-Pelagianism was rife in the populace–a quasi-Protestant set of beliefs one clergyman called “country divinity”.

William Whittingham was probably the most prominent leader of the movement at this early phase. He was among those who had spent time in Calvin’s Geneva during the reign of Mary I, and who now sought to bring Genevan influences to bear in the English Church. Some individuals joined the clergy in order to promote reform; others chose to remain outside the episcopal establishment. Many reform-minded ministers began to meet in small groups for mutual edification, after the pattern of the Continental Protestant churches’ presbyterian assemblies.

From the beginning, puritan ministers were supported by wealthy gentry who were sympathetic to their cause. Within the queen’s court, the puritans had good friends in Francis Russell, earl of Bedford, and Robert Dudley, earl of Leicester. A number of gentry sent their children to be educated by puritan instructors in the universities.

Part Two: The Breach Opens

Chapters:

- ‘So Many Learned and Religious Bishops’

- ‘That Comical Dress’

- London’s Protestant Underground

- The People and the Pope’s Attire

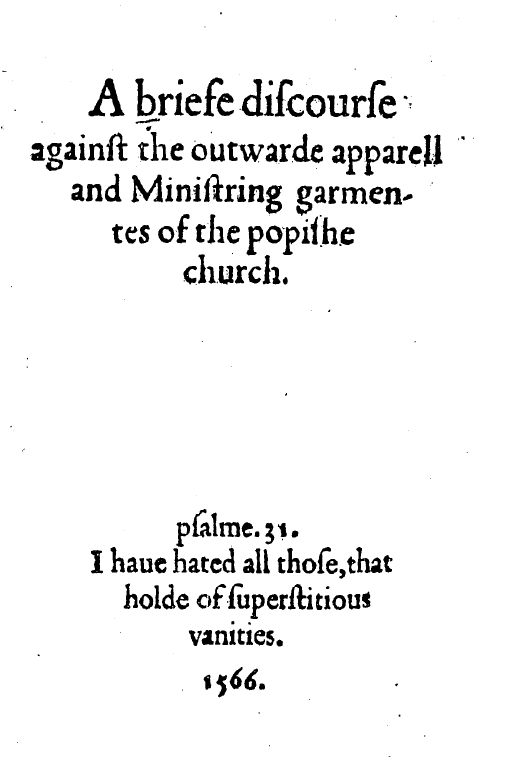

In the years immediately following Elizabeth’s accession, the English Church’s more progressive, reform-minded bishops were able to interpret the Elizabethan Religious Settlement as they wished. Differences of opinion soon came to the fore, however, in what became known as the Vestments Controversy (1563-67). The queen and her archbishop, Matthew Parker, stipulated that all clergy were to wear the square cap, gown, tippet, and surplice, or be suspended. In March 1565, several refused to comply and were suspended, though before long, most did subscribe. The most obdurate protests came from Robert Crowley, John Philpot, John Gough and Percival Wiburn. The first puritan manifestoes (see one example, right) were printed and disseminated during these years.

In the years immediately following Elizabeth’s accession, the English Church’s more progressive, reform-minded bishops were able to interpret the Elizabethan Religious Settlement as they wished. Differences of opinion soon came to the fore, however, in what became known as the Vestments Controversy (1563-67). The queen and her archbishop, Matthew Parker, stipulated that all clergy were to wear the square cap, gown, tippet, and surplice, or be suspended. In March 1565, several refused to comply and were suspended, though before long, most did subscribe. The most obdurate protests came from Robert Crowley, John Philpot, John Gough and Percival Wiburn. The first puritan manifestoes (see one example, right) were printed and disseminated during these years.Both proponents and opponents of vestments appealed to Protestant leaders in Geneva (Theodore Beza) and Zurich (Rodolph Gualter). Beza took a fairly moderate stance, urging dissidents in England to comply with official policy, while continuing to preach against vestments.

During the 1560s, a group of separatists and semi-separatists formed in London, in the Minories, Plumbers Hall and other areas. They were led by preachers John Field and Thomas Wilcox, and by other figures who were not affiliated with the state church. In 1567, around one hundred of their number were incarcerated because of their unsanctioned meetings. Many then became full-blown separatists.

Puritanism gained a fairly strong foothold among both laymen and -women; the latter, in fact, gave considerable strength to the movement. Puritan layfolk came to refer to themselves as “the godly”. For many of them, the clerical cap and surplice brought memories of the reign of Mary I, still fairly recent, when Catholic bishops and priests supervised the grisly execution of many Protestant martyrs. Negative images of Rome like this helped to foster views sympathetic to puritanism among the populace.

Parts 3-4 coming soon . . .

2 comments:

Hi. I recently purchased an original hardback copy of this book. I'm hoping to fit it into my reading schedule 'somehow' in the near future. I appreciate the puritan themed blog; it is a movement I am gradually learning about and therefore appreciating more!

May God bless the effect of this blog.

Thanks, Bob! I hope to finish this summary of Collinson's book. It's definitely a seminal scholarly introduction to early puritanism.

Post a Comment