Dangerous Puritans?

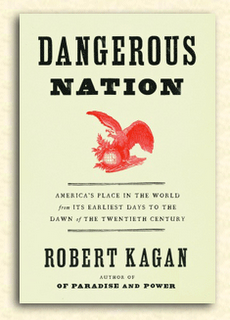

Max Boot, political analyst and columnist for the LA Times, the Weekly Standard and other publications, recently reviewed a new book by Robert Kagan called Dangerous Nation: America's Place in the World from its Earliest Days to the Dawn of the Twentieth Century. Kagan challenges those who would describe the United States' foreign policy as aloof and isolationist, claiming Americans have been driven by "a desire to spread liberty at the point of a gun" ever since ... you guessed it, ever since the first Puritans came to New England. Writes Boot:

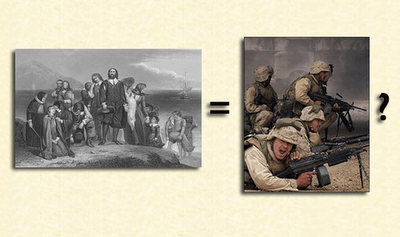

Max Boot, political analyst and columnist for the LA Times, the Weekly Standard and other publications, recently reviewed a new book by Robert Kagan called Dangerous Nation: America's Place in the World from its Earliest Days to the Dawn of the Twentieth Century. Kagan challenges those who would describe the United States' foreign policy as aloof and isolationist, claiming Americans have been driven by "a desire to spread liberty at the point of a gun" ever since ... you guessed it, ever since the first Puritans came to New England. Writes Boot:Wrongly interpreted as isolationists who wanted to escape the world by building a "city upon a hill," the Puritans were actually, in Kagan's telling, "global revolutionaries" who came to the New World to establish a base from which they could convert the Old World. Other early settlers were less religious and more animated by what Kagan calls "acquisitive materialism." Neighbors who might block their acquisitions — whether Indians or Spaniards — were brushed aside or attacked.

I haven't read Kagan's book yet, but the explanation of the New England settlers' motives above is basically accurate, in my understanding. Some questions that I pondered after reading Boot's review, about which I invite comment:

- How much weight should historians put on the concept of 'precedent' in any nation's foreign policy? In other words, can and do things like 'a desire to spread liberty at the point of a gun' really pass from generation to generation, even from one (important) subculture within a nation to others over time, as suggested here in the case of the Puritans and their national descendants? Does the decision of the U. S. to invade Iraq really have anything to do with the advent of the Puritans 370 years prior? I'm not saying it does or doesn't, just pondering; and,

- Is any cause worth spreading by coercion? For instance, if a strong and democratic nation is within reasonable proximity to a militarily weaker nation that is being cruelly oppressed by a tyrant, and the stronger nation has the ability (according to its best evaluations) to topple the tyrant and establish a society in which there is a significantly greater amount of liberty for its citizens, then is it ethically justified or even obligated to do so?; and if it is (either of those), at what point does the cost of such a venture, in terms of either casualties or money, become prohibitive?

No comments:

Post a Comment